Research Journal for Veterinary Practitioners

Case Report

Research Journal for Veterinary Practitioners 2 (1): 17 – 18Surgical Treatment of Penile Prolapse in a Red Eared Slider (Trachemys Scripta Elegans)

Musa Korkmaz*, Zulfikar Kadir Saritas, İbrahim Demirkan

*Corresponding author: musakorkmaz@aku.edu.tr

ARTICLE CITATION:

Korkmaz M, Saritas ZK, Demirkan I (2014). Surgical treatment of penile prolapse in a red eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans). Res. j. vet. pract. 2 (1): 17 – 18.

Received: 2013–12–03, Revised: 2013–12–18, Accepted: 2013–12–23

The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at

(http://dx.doi.org/10.14737/journal.rjvp/2014/2.1.17.18)

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

This study was designed to describe a rarely seen case of penile prolapse and its surgical treatment in a red eared slider (RES). A 7–year–old male RES, weighing 230 gr was referred to the university animal hospital with complaint of a black mass formation, emerging from the anus which noted two days ago. In clinical examination, the mass was prolapsed penis showing insensitivity and necrosis. Therefore, the amputation of penis was carried out by surgical intervention. In conclusion, the surgical treatment of a rarely seen penile prolapse case in SER was reported.

Male chelonians have a single copulatory organ, the penis (phallus), which is solid tissue and has no lumen (Norton, 1994; Barten, 2006). This organ is large and fleshy and varies in colour from pink to deep purple to black, depending on the species. Normally, the penis is retracted within the cloacae and lies on the ventral floor of the proctodeum. Penis or hemipenes contains a urethra and these organs are not used for urination (Barten, 2006).

Penile prolapse may occur in chelonians and snakes and lizards (Barten, 2006) and is rarely seen in chelonians. Prolapsed penis may be associated with traumas, such as bite wounds from cage mates, traction during copulation, infection, inflammation, nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism, neurologic or traumatic deficits involving the retractor penis muscles or cloacal sphincter, and straining from intestinal parasites, impaction of the cloaca with gastrointestinal foreign bodies (sand, bark chips, or gravel), or bladder or cloacal uroliths (Norton, 1994; Boyer, 1998; Barten, 2006). Beside the predisposing factors of prolapsed penis in chelonians is frequent, its surgical treatment and post–operative process is not clear in veterinary practice. Thus we describe here a rarely seen case of penile prolapse and its surgical treatment in a RES.

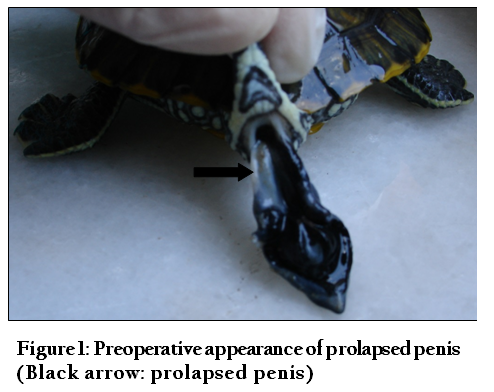

A 7–year–old male RES, weighing 230 gr was referred to the university animal hospital with complaint of black mass formation sticking out from the anus. The owner noted that this tissue protruded after mating two days ago. Loss of appetite was observed at the next day after mating, but defecation and urination was normal. Close examination revealed that the protruding mass from the anus was prolapsed penis (Figure 1). The penis was insensitive to pin prick and the necrosis was observed. Then, it was decided that RES was candidate to surgical amputation of the penis.

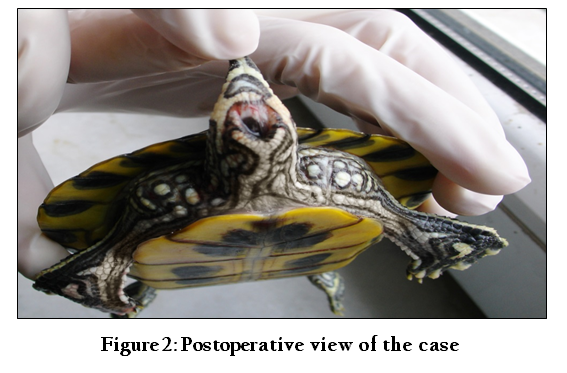

The induction of general anaesthesia was performed by intramuscular administration of 20 mg/kg ketamine (Alfamine, Egevet, Turkey). After induction of anaesthesia, uncuffed endotracheal tube was placed (2.0 mm). Oxygen and isoflurane 2 % (Forane, Abbot, Turkey) was given (Longley, 2008). Under the general anaesthesia, the base of the penis was ligated by transfixational technique with polyglactin 910 3/0 (Vicryl, Ethicon, Turkey) and then necrotic phallus was removed. The remainder penis tissue was replaced into its normal anatomical position (Figure 2).

Enrofloxacin (10 mg/kg) (Baytril K 5 %, Bayer, Turkey) was administered intramuscularly for 5 consecutive days postoperatively. During post–operative process, no complications associated with feed intake, urination and defecation were observed.

The presence of penis prolapse in chelonians is documented in veterinary textbooks (Norton, 1994; Barten, 2006), however, there is limited reports in veterinary literature (Sharma and Raghuvanshi, 2009; Nisbet et al., 2011). Penile prolapses may be results of infection, forced separation during copulation, inflammation, nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism, neurologic or traumatic defects involving the retractor penis muscles or cloacal sphincter, and straining from intestinal parasites, impaction of the cloaca with gastrointestinal foreign bodies (Norton, 1994; Barten, 2006). Nisbet et al., (2011) reported that penis prolapse in a RES was occurred after copulation. In this case, it was considered that prolapse of penis might be caused by following mating as mentioned by the owner.

It has been indicated that in such cases, where the penis tissue is still considered viable, the organ may be reduced. Before reducing the prolapsed tissue, it should be cleaned and any lacerations repaired. Moreover, the presence of oedema may be controlled with the application of cold compresses (Norton, 1994; Barten, 2006). Raut et al., (2008) also reported that Estriol cream can be applied to reduce the possible hormone dependant congestion. However, the prolapsed penis should be amputated where the prolapsed phallus is necrotic (Norton, 1994; Barten, 2006; Ojeh and Adetunji, 2008; Nisbet et al., 2011). In the present case, it was decided that the amputation of penis was a straight approach due to insensitivity and necrosis of penile tissue.

The surgical treatment of a rarely seen penile prolapse case in RES was reported and can be practiced without life–threatening complications in the field.

REFERENCES

Barten SL (2006). Penile Prolapse In: Mader DR (editor), Reptile Medicine and Surgery, 2nd ed., WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 862–864. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B0-72-169327-X/50068-7

Boyer TH (1998). Emergency care of reptiles. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Exotic Anim. Prac. 1: 191–206. PMid:11228723

Longley LA (2008). Anaesthesia of Exotic Pets, 1st edition, Saunders, Elsevier, Philadelphia, 228–237. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-2888-5.50016-2

Nisbet HO, Yardımcı C, Ozak and Sirin YS (2011). Penile Prolapse in A Red Eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans). Kafkas Üni. Vet. Fak. Derg. 17: 151–153.

Norton TM (1994). Chelonian Emergency and Critical Care. Semin. Avian Exot. Pet. Med. 14: 106–130. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.saep.2005.04.005

Ojeh CK and Adetunji A (2008). Penile prolapse in a tortoise (Testudo gigantea). Afr. J. Ecol. 18 (2–3): 187–190.

Raut BM, Raghuwanshi DS, Upadhye SV, Gahlod BM, Khante GS and Borghare AP (2008). Hormonal management of rectal prolapse in a turtle. Vet. World. 1(8): 248.

Sharma YK and Raghuvanshi PDS (2009). Surgical treatment of cloacal prolapse in a turtle. Indian J. Vet. Surg. 30: 70